By MANOHLA DARGIS

Published: October 23, 2009

Amelia Earhart, the American aviator who disappeared somewhere over the Pacific in 1937 while trying to become the first woman to fly around the globe, didn’t wear bodices, as far as I can tell from the new biographical movie starring Hilary Swank. If Earhart had, it’s a good bet that Richard Gere, who plays her sensitive, supportive, quietly suffering husband, George Palmer Putnam (G. P.), would have ripped or, rather, politely removed an unmentionable or two amid the civilized yearning and the surging, swelling music.

Romance is in the air in “Amelia,” or at least in the score, which works hard to inject some emotional coloring into the proceedings. The music screams (sobs) 1940s big-screen melodramatic excess and beautiful suffering.

Alas, excesses of any pleasurable kind are absent from this exasperatingly dull production. The director Mira Nair, whose only qualification appears to be that she’s a woman who has made others films about and with women (“Mississippi Masala,” “Vanity Fair”), keeps a tidy screen — it’s all very neat and carefully scrubbed. I don’t recall a single dented automobile or a fissure of real feeling etched into a face. Bathed in golden light, Amelia and G. P. are as pretty as a framed picture and as inert.

Earhart became a celebrity during her two decades in the air, setting records and grabbing headlines. In 1928 she became the first woman to fly across the Atlantic. She wasn’t allowed to pilot the plane, forced instead to watch the world pass by from the rear. (“I was just baggage.”) Four years later she took the controls to become the first woman to fly solo across the pond. She then tried to circle the globe: “Like previous flights, I am undertaking this one solely because I want to, and because I feel that women now and then have to do things to show what women can do.” And then there was this: “I am going for the fun. Can you think of a better reason?”

Well, no, I can’t, though fun — along with nonpharmaceutical kicks and just the pleasures that come with being alive — doesn’t often factor into recent film biographies, especially of stars, perhaps because filmmakers think we need tears to wash down the achievements.

No triumph goes unpunished in “Ray” or “Walk the Line.” An American film that does suggest that bliss can figure in remarkable lives is “I’m Not There,” Todd Haynes’s fractured portrait of Bob Dylan, though even here the highest highs are in the filmmaking itself. Gus Van Sant’s “Milk,” about the gay-rights advocate Harvey Milk, conveys its subject’s joy, but that exuberance is the beatific prelude to martyrdom.

Earhart wasn’t a martyr. She vanished doing what she loved best: touching the clouds. At the time she was 39, seemingly content in her marriage or at peace with its compromises, and publicly adored. An argument can be made that her death was a catastrophe — a husband lost a wife and the world a feminist inspiration — but “Amelia” won’t or can’t rise to the tragic occasion. The filmmakers spend so much time turning her into a dopey romantic figure that they never give her the animating, vital will or even much of a personality that might explain how a Kansas tomboy turned Boston social worker took to the skies and then, through her deeds and words, encouraged other women to chart their own courses.

She did marry, at 33. Ms. Nair recreates the simple ceremony — like many biopic directors, she dutifully spins all the greatest hits — and shares Earhart’s remarkable prenuptial letter to G. P. “I shall not hold you to any medieval code of faithfulness to me nor shall I consider myself bound to you similarly,” Earhart wrote. “Please let us not interfere with the other’s work or play.” The movie, like some biographies, reveals that some of that play involved an aviation entrepreneur, Gene Vidal (Ewan McGregor, smiley and, perhaps, self-consciously artificial), whose young son, a future writer named Gore (William Cuddy), asked her to marry his father. This affair, though, scarcely registers before she’s safely back in the marital fold.

The emphasis on her marriage domesticates Earhart and also turns her into a bore. Instead of digging deep into the complexities of her character (as Mr. Haynes does with Mr. Dylan), the filmmakers cram Earhart’s life — or at least its presumptive highlights — into a biographical template. In this mold, familiar from many Hollywood and Hollywood-inspired movies, the thickness of life is thinned until it’s as manageable and as easy to shoot and to sell as a bulleted checklist. Amelia flies. Amelia meets G. P. Amelia flies again. Amelia marries G. P. Amelia flies once more. And so forth and so on, with the requisite period details (cue the jazz music and scratchy black-and-white newsreels) adding visual interest.

With her rangy figure, Ms. Swank fills Earhart’s coveralls and leather jackets nicely. But there’s little to the performance other than the actress’s natural earnestness and smiles so enormous, persistent and consuming that the rest of Earhart soon fades, much like the Cheshire Cat. As usual, Mr. Gere holds your attention with beauty and a screen presence so recessive that it creates its own gravitational pull.

The actors don’t make a persuasive fit, despite all their long stares and infernal smiling. (The movie is a more effective testament to the triumphs of American dentistry than to Earhart or aviation.) It’s hard to imagine anyone, other than satirists, doing anything with the puerile, sometimes risible dialogue. The screenwriters, Ron Bass and Anna Hamilton Phelan, give Earhart a voice-over even as they forget her voice.

“Amelia” is rated PG (Parental guidance suggested). She smokes, she flies and most likely dies.

AMELIA

Opens on Friday nationwide.

Directed by Mira Nair; written by Ron Bass and Anna Hamilton Phelan, based on the books “East to the Dawn” by Susan Butler and “The Sound of Wings” by Mary S. Lovell; director of photography, Stuart Dryburgh; edited by Allyson C. Johnson and Lee Percy; music by Gabriel Yared; production designer, Stephanie Carroll; produced by Ted Waitt, Kevin Hyman and Lydia Dean Pilcher; released by Fox Searchlight Pictures. Running time: 1 hour 51 minutes.

WITH: Hilary Swank (Amelia Earhart), Richard Gere (George Palmer Putnam), Ewan McGregor (Gene Vidal), William Cuddy (Gore Vidal), Christopher Eccleston (Fred Noonan), Joe Anderson (Bill), Cherry Jones (Eleanor Roosevelt) and Mia Wasikowska (Elinor Smith).

Tuesday, October 27, 2009

Some of His Best Friends Are Beasts

Some of His Best Friends Are Beasts

By MANOHLA DARGIS

Published: October 16, 2009

Most of the snuffling, growling beasts that roam and often stomp through “Where the Wild Things Are,” Spike Jonze’s alternately perfect and imperfect if always beautiful adaptation of the Maurice Sendak children’s book, come covered in fur. Some have horns; most have twitchy tails and vicious-looking teeth. The beasts snarl and howl and sometimes sniffle. One has a runny nose. Yet another has pale, smooth skin and the kind of large, wondering eyes that usually grow smaller and less curious with age. This beast is Max, the boy in the wolf costume who one night slips into the kind of dream the movies were made for.

\

“Let the wild rumpus start!” Max (back to camera) reigns as the king of the wild things in a scene from the movie.

Multimedia

Warner Brothers Pictures

Max arriving on an island populated by hairy beasts “with terrible claws.”

Max, played by the newcomer Max Records, is the pivotal character in this intensely original and haunting movie, though by far the most important figure here proves to be Mr. Jonze. After years in the news, the project and its improbability — a live-action movie based on a slender, illustrated children’s book that runs fewer than 40 pages, some without any words at all — are no longer a surprise. Even so, it startles and charms and delights largely because Mr. Jonze’s filmmaking exceeds anything he’s done in either of his inventive previous features, “Being John Malkovich” (1999) and “Adaptation” (2002). With “Where the Wild Things Are” he has made a work of art that stands up to its source and, in some instances, surpasses it.

First published in 1963, the book follows the adventures of Max, who looks to be about 6 (he’s closer to 9 in the movie) and enters making mischief “of one kind and another” while dressed in a wolf suit with a long, bushy tail and a hood with ears and whiskers. After his unseen mother calls him “wild thing!” and he threatens to eat her up, he is sent to his room without dinner. But his room magically transforms into a forest and, finding a boat, he sails to a place populated by giant, hairy, scary beasts that make him their king. Eventually the tug of home pulls him back to his room, where supper (“still hot”) sits waiting.

There are different ways to read the wild things, through a Freudian or colonialist prism, and probably as many ways to ruin this delicate story of a solitary child liberated by his imagination. Happily, Mr. Jonze, who wrote the screenplay with Dave Eggers, has not attempted to enlarge or improve the story by interpreting it. Rather, he has expanded it, very gently. The movie is still a story about a boy, his mother, his room, his loneliness and various wild things of his creation. But now there are new details and shadings to complement the book’s material, like Max’s older sister, Claire (Pepita Emmerichs), whose lank hair and adolescent gloom are touchingly mirrored by a wild thing named K W (voiced by Lauren Ambrose).

Like Mr. Sendak’s unruly boy, the movie’s Max is a storm without warning, throwing himself into the story while noisily chasing the family dog down some stairs. Shot with a handheld camera that can barely contain the boy’s image inside the frame, these clattering, jangling introductory moments are disruptive, disorienting — it’s hard to see exactly where Max and the dog are as you all tumble down — and purely exhilarating. Yet after jolting the story to excited life, Mr. Jonze quiets the movie down for a series of flawlessly calibrated scenes of Max alone and with his sister and mother (Catherine Keener), an interlude that tells you everything you need to know about the boy and that announces all that will happen next.

These scenes, lasting 20 minutes or so, are achingly intimate and tender. Mr. Jonze, working with his regular cinematographer, Lance Acord, brings you close into Max’s world as he builds an igloo in the street, starts a snowball fight with Claire’s friends and is left to weep alone after the igloo is destroyed. (When Max slides into the igloo, the camera is right there, which means that you’re there too when disaster strikes.) The world is cruel, children too, lessons that Max absorbs through a smear of tears and hurt. The wound doesn’t heal. Max clomps and then stomps and then erupts: he roars at his mother. She roars back. And, then, like his storybook counterpart — like everyone else — he sails into the world, adrift and alone.

This is the existential given at the heart of both Mr. Sendak’s book and Mr. Jonze’s movie, which might come as a surprise to anyone who misremembers the original, with its dark, crosshatched lines; spiky emotions; Max’s many frowns; and the “terrible teeth” and “terrible claws” of the creatures. Though their conceptual bite remains sharply intact, Mr. Jonze’s wild things are softer, cuddlier-looking than the drawn ones because they have partly been brought to waddling life by performers in outsize costumes. (The fluid tremors of emotion enlivening the fuzzy faces were primarily created through computer-generated animation.) The vexed, whining, caressing voices — James Gandolfini as Carol, Catherine O’Hara as Judith, Forest Whitaker as Ira, Paul Dano as Alexander and Chris Cooper as Douglas — do the expressive rest.

Max discovers the wild things on an island, destroying their homes in fury and for kicks. Introductions are made, wary sniffs exchanged. But these are his kind of beasts, after all, and so, amid the rough splendor of a primeval forest where the air swirls with pink petals and snowflakes, he becomes their king. “Let the wild rumpus start!” he yells, as all the creatures, Max now included, rampage. It’s all very new (and scary) but also vaguely familiar, because we’ve seen it before. The tantrums, tears and angry words from the film’s first 20 minutes all start to resurface during this idyll, much as our waking hours invade our dreams: the snowball fight is recast as a dirt-clod battle. Max plays the angry child and then the reproving parent.

Much is left unexplained in Mr. Jonze’s adaptation, including Max’s melancholia, which hangs over him, his family and his wild things like a gathering storm. But childhood has its secrets, mysteries, small and large terrors. When a hilariously bungling teacher explains, rather too casually, that the sun is going to die, the flash of horror on Max’s face indicates that he understands that the sun won’t be the only one to go. There are other reasons, perhaps, an absent father, a distracted mother. (And when a frightened Max listens to an argument between Carol and K W, you hear the echoes of parental discord.) But such analysis is for therapy, not art, and one of the film’s pleasures is its refusal of banal explanation.

On occasion, Mr. Jonze lingers too long on his lovely pictures, particularly on the island, where the film’s energy starts to wane, despite the glorious whoops in Carter Burwell and Karen O’s score. Mr. Jonze loves Max’s wild things, but you don’t need to hang around long to adore them as well. Yet these are minor complaints about a film that often dazzles during its quietest moments, as when Max sets sail, and you intuit his pluck and will from the close-ups of him staring into the unknown. He looms large here, as we do inside our heads. But when the view abruptly shifts to an overhead shot, you see that the boat is simply a speck amid an overwhelming vastness. This is the human condition, in two eloquent images.

“Where the Wild Things Are” is rated PG (Parental guidance suggested). The wild things in the movie have been designed and directed toward a distinctly older age group than the book’s original audience. If monsters give you the willies, beware!

WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE

Opens on Friday nationwide. Directed by Spike Jonze; written by Mr. Jonze and Dave Eggers, based on the book by Maurice Sendak; director of photography, Lance Acord; edited by Eric Zumbrunnen and James Haygood; music by Karen O and Carter Burwell; production designer, K. K. Barrett; produced by Tom Hanks, Gary Goetzman, John B. Carls, Mr. Sendak and Vincent Landay; released by Warner Brothers Pictures. Running time: 1 hour 40 minutes.

WITH: Max Records (Max), Catherine Keener (Mom), Mark Ruffalo (Boyfriend), Lauren Ambrose (KW), Chris Cooper (Douglas), James Gandolfini (Carol), Catherine O’Hara (Judith), Forest Whitaker (Ira), Paul Dano (Alexander) and Pepita Emmerichs (Claire).

By MANOHLA DARGIS

Published: October 16, 2009

Most of the snuffling, growling beasts that roam and often stomp through “Where the Wild Things Are,” Spike Jonze’s alternately perfect and imperfect if always beautiful adaptation of the Maurice Sendak children’s book, come covered in fur. Some have horns; most have twitchy tails and vicious-looking teeth. The beasts snarl and howl and sometimes sniffle. One has a runny nose. Yet another has pale, smooth skin and the kind of large, wondering eyes that usually grow smaller and less curious with age. This beast is Max, the boy in the wolf costume who one night slips into the kind of dream the movies were made for.

\

“Let the wild rumpus start!” Max (back to camera) reigns as the king of the wild things in a scene from the movie.

Multimedia

Warner Brothers Pictures

Max arriving on an island populated by hairy beasts “with terrible claws.”

Max, played by the newcomer Max Records, is the pivotal character in this intensely original and haunting movie, though by far the most important figure here proves to be Mr. Jonze. After years in the news, the project and its improbability — a live-action movie based on a slender, illustrated children’s book that runs fewer than 40 pages, some without any words at all — are no longer a surprise. Even so, it startles and charms and delights largely because Mr. Jonze’s filmmaking exceeds anything he’s done in either of his inventive previous features, “Being John Malkovich” (1999) and “Adaptation” (2002). With “Where the Wild Things Are” he has made a work of art that stands up to its source and, in some instances, surpasses it.

First published in 1963, the book follows the adventures of Max, who looks to be about 6 (he’s closer to 9 in the movie) and enters making mischief “of one kind and another” while dressed in a wolf suit with a long, bushy tail and a hood with ears and whiskers. After his unseen mother calls him “wild thing!” and he threatens to eat her up, he is sent to his room without dinner. But his room magically transforms into a forest and, finding a boat, he sails to a place populated by giant, hairy, scary beasts that make him their king. Eventually the tug of home pulls him back to his room, where supper (“still hot”) sits waiting.

There are different ways to read the wild things, through a Freudian or colonialist prism, and probably as many ways to ruin this delicate story of a solitary child liberated by his imagination. Happily, Mr. Jonze, who wrote the screenplay with Dave Eggers, has not attempted to enlarge or improve the story by interpreting it. Rather, he has expanded it, very gently. The movie is still a story about a boy, his mother, his room, his loneliness and various wild things of his creation. But now there are new details and shadings to complement the book’s material, like Max’s older sister, Claire (Pepita Emmerichs), whose lank hair and adolescent gloom are touchingly mirrored by a wild thing named K W (voiced by Lauren Ambrose).

Like Mr. Sendak’s unruly boy, the movie’s Max is a storm without warning, throwing himself into the story while noisily chasing the family dog down some stairs. Shot with a handheld camera that can barely contain the boy’s image inside the frame, these clattering, jangling introductory moments are disruptive, disorienting — it’s hard to see exactly where Max and the dog are as you all tumble down — and purely exhilarating. Yet after jolting the story to excited life, Mr. Jonze quiets the movie down for a series of flawlessly calibrated scenes of Max alone and with his sister and mother (Catherine Keener), an interlude that tells you everything you need to know about the boy and that announces all that will happen next.

These scenes, lasting 20 minutes or so, are achingly intimate and tender. Mr. Jonze, working with his regular cinematographer, Lance Acord, brings you close into Max’s world as he builds an igloo in the street, starts a snowball fight with Claire’s friends and is left to weep alone after the igloo is destroyed. (When Max slides into the igloo, the camera is right there, which means that you’re there too when disaster strikes.) The world is cruel, children too, lessons that Max absorbs through a smear of tears and hurt. The wound doesn’t heal. Max clomps and then stomps and then erupts: he roars at his mother. She roars back. And, then, like his storybook counterpart — like everyone else — he sails into the world, adrift and alone.

This is the existential given at the heart of both Mr. Sendak’s book and Mr. Jonze’s movie, which might come as a surprise to anyone who misremembers the original, with its dark, crosshatched lines; spiky emotions; Max’s many frowns; and the “terrible teeth” and “terrible claws” of the creatures. Though their conceptual bite remains sharply intact, Mr. Jonze’s wild things are softer, cuddlier-looking than the drawn ones because they have partly been brought to waddling life by performers in outsize costumes. (The fluid tremors of emotion enlivening the fuzzy faces were primarily created through computer-generated animation.) The vexed, whining, caressing voices — James Gandolfini as Carol, Catherine O’Hara as Judith, Forest Whitaker as Ira, Paul Dano as Alexander and Chris Cooper as Douglas — do the expressive rest.

Max discovers the wild things on an island, destroying their homes in fury and for kicks. Introductions are made, wary sniffs exchanged. But these are his kind of beasts, after all, and so, amid the rough splendor of a primeval forest where the air swirls with pink petals and snowflakes, he becomes their king. “Let the wild rumpus start!” he yells, as all the creatures, Max now included, rampage. It’s all very new (and scary) but also vaguely familiar, because we’ve seen it before. The tantrums, tears and angry words from the film’s first 20 minutes all start to resurface during this idyll, much as our waking hours invade our dreams: the snowball fight is recast as a dirt-clod battle. Max plays the angry child and then the reproving parent.

Much is left unexplained in Mr. Jonze’s adaptation, including Max’s melancholia, which hangs over him, his family and his wild things like a gathering storm. But childhood has its secrets, mysteries, small and large terrors. When a hilariously bungling teacher explains, rather too casually, that the sun is going to die, the flash of horror on Max’s face indicates that he understands that the sun won’t be the only one to go. There are other reasons, perhaps, an absent father, a distracted mother. (And when a frightened Max listens to an argument between Carol and K W, you hear the echoes of parental discord.) But such analysis is for therapy, not art, and one of the film’s pleasures is its refusal of banal explanation.

On occasion, Mr. Jonze lingers too long on his lovely pictures, particularly on the island, where the film’s energy starts to wane, despite the glorious whoops in Carter Burwell and Karen O’s score. Mr. Jonze loves Max’s wild things, but you don’t need to hang around long to adore them as well. Yet these are minor complaints about a film that often dazzles during its quietest moments, as when Max sets sail, and you intuit his pluck and will from the close-ups of him staring into the unknown. He looms large here, as we do inside our heads. But when the view abruptly shifts to an overhead shot, you see that the boat is simply a speck amid an overwhelming vastness. This is the human condition, in two eloquent images.

“Where the Wild Things Are” is rated PG (Parental guidance suggested). The wild things in the movie have been designed and directed toward a distinctly older age group than the book’s original audience. If monsters give you the willies, beware!

WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE

Opens on Friday nationwide. Directed by Spike Jonze; written by Mr. Jonze and Dave Eggers, based on the book by Maurice Sendak; director of photography, Lance Acord; edited by Eric Zumbrunnen and James Haygood; music by Karen O and Carter Burwell; production designer, K. K. Barrett; produced by Tom Hanks, Gary Goetzman, John B. Carls, Mr. Sendak and Vincent Landay; released by Warner Brothers Pictures. Running time: 1 hour 40 minutes.

WITH: Max Records (Max), Catherine Keener (Mom), Mark Ruffalo (Boyfriend), Lauren Ambrose (KW), Chris Cooper (Douglas), James Gandolfini (Carol), Catherine O’Hara (Judith), Forest Whitaker (Ira), Paul Dano (Alexander) and Pepita Emmerichs (Claire).

Monday, October 26, 2009

Sunday, October 25, 2009

dream

i was in a automotive store or the automotive section of a department store like K mart. I was asking for a cap to cover fuel tank or place on the car where the liquids go. There were three different ones on the car. Two clerks were helping me and they were trying to find the one I needed. they brought me winter coats but I needed gas caps. I tried to tell them I needed caps. I knew I was away from home and travelling on the road.

This is the second dream that my friend Dar was around the dream. I may have been travelling with her but in my own car. My last dream about travelling had Dar in the aspect of this one. I knew she was around the dream but not in the dream. I am not sure if her son was around this one. Something makes me think Stephan was around this dream or that I met up with her and stephen in a park area where there a festival or carnival and he was there. It was a like a circus of sorts. We were overwhelmed with colors and with things to look at.

This is the second dream that my friend Dar was around the dream. I may have been travelling with her but in my own car. My last dream about travelling had Dar in the aspect of this one. I knew she was around the dream but not in the dream. I am not sure if her son was around this one. Something makes me think Stephan was around this dream or that I met up with her and stephen in a park area where there a festival or carnival and he was there. It was a like a circus of sorts. We were overwhelmed with colors and with things to look at.

Dream 10-22-09

I was travelling with two women. They appeared to be the women from the training team that I will we working on. They are both African Americans. We entered this rural tropical bar/restaurants like the ones in the South Pacific depicted in Movies. Like in a tiki hut. There was a bartender who was addressing people as they were coming in. My travelling companions took a place at the bar. They were waiting for a tour to start. In came an African woman who sat at the bar. Her name was on the chalk board behind the bartender and he reminded her that has been there previously. In the dream, I knew that the hash marks were a count of the illegal abortions that the woman had. He was a conduit to illegal abortions. He monitored the women and set them up as they entered the establishment. I was in the backroom with a white man and we were working on cleaning up a toilet bowl. We were using bleach. He was pouring and I was using a toilet brush. We were talking back and forth.

I returned to the bar area to find my colleagues were waiting for me while I was killing time waiting for them. There was a miscommunication or error in the communication. Between us. Sometimes in the dream, they were other people as well but there were two women whom I had a misunderstanding of communication with.

I was travelling with two women. They appeared to be the women from the training team that I will we working on. They are both African Americans. We entered this rural tropical bar/restaurants like the ones in the South Pacific depicted in Movies. Like in a tiki hut. There was a bartender who was addressing people as they were coming in. My travelling companions took a place at the bar. They were waiting for a tour to start. In came an African woman who sat at the bar. Her name was on the chalk board behind the bartender and he reminded her that has been there previously. In the dream, I knew that the hash marks were a count of the illegal abortions that the woman had. He was a conduit to illegal abortions. He monitored the women and set them up as they entered the establishment. I was in the backroom with a white man and we were working on cleaning up a toilet bowl. We were using bleach. He was pouring and I was using a toilet brush. We were talking back and forth.

I returned to the bar area to find my colleagues were waiting for me while I was killing time waiting for them. There was a miscommunication or error in the communication. Between us. Sometimes in the dream, they were other people as well but there were two women whom I had a misunderstanding of communication with.

Saturday, October 24, 2009

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Capricorn Horoscope for week of October 22, 2009

Capricorn Horoscope for week of October 22, 2009

It's prime time for intense and momentous social events. Of the gatherings you may attend, I hope you'll find at least one that fits the following descriptions: 1. a warm fluidic web of catalytic energy where you awaken to new possibilities about how to create close alliances; 2. a sweet, jangly uproar where you encounter a strange attractor -- a freaky influence that makes the hair on the back of your neck rise and lights up the fertile parts of your imagination; 3. a sacred party where you get a novel vision of how to connect with the divine realms more viscerally. Halloween costume suggestion: something that incorporates a hub, wheel, or web.

It's prime time for intense and momentous social events. Of the gatherings you may attend, I hope you'll find at least one that fits the following descriptions: 1. a warm fluidic web of catalytic energy where you awaken to new possibilities about how to create close alliances; 2. a sweet, jangly uproar where you encounter a strange attractor -- a freaky influence that makes the hair on the back of your neck rise and lights up the fertile parts of your imagination; 3. a sacred party where you get a novel vision of how to connect with the divine realms more viscerally. Halloween costume suggestion: something that incorporates a hub, wheel, or web.

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

Capricorn Horoscope for week of October 15, 2009

Capricorn Horoscope for week of October 15, 2009

Verticle Oracle card Capricorn (December 22-January 19)

"There are two rules for ultimate success in life," wrote L. M. Boyd. "First, never tell everything you know." While that may be the conventional wisdom about how to build up one's personal power, I prefer to live by a different principle. Personally, I find that as I divulge everything I know, I keep knowing more and more that wasn't available to me before. The act of sharing connects me to fresh sources. Open-hearted communication doesn't weaken me, but just the reverse: It feeds my vitality. This is the approach I recommend to you in the coming days, Capricorn. Do indeed tell everything you know.

Verticle Oracle card Capricorn (December 22-January 19)

"There are two rules for ultimate success in life," wrote L. M. Boyd. "First, never tell everything you know." While that may be the conventional wisdom about how to build up one's personal power, I prefer to live by a different principle. Personally, I find that as I divulge everything I know, I keep knowing more and more that wasn't available to me before. The act of sharing connects me to fresh sources. Open-hearted communication doesn't weaken me, but just the reverse: It feeds my vitality. This is the approach I recommend to you in the coming days, Capricorn. Do indeed tell everything you know.

Oleanna

He Said, She Said, but What Exactly Happened?

*

Article Tools Sponsored By

By BEN BRANTLEY

Published: October 12, 2009

Here’s a little physics puzzle for John, the university professor from David Mamet’s “Oleanna” and a man who practically breaks his neck by bending it to consider questions from different angles: How is it possible that two productions of the same play — occupying roughly the same amount of stage time and using almost exactly the same words — can move at such vastly different speeds?

Skip to next paragraph

Enlarge This Image

Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

"Oleanna": Julia Stiles and Bill Pullman in a revival of the David Mamet play, at the Golden Theater.

Related

ArtsBeat: Q&A: Bill Pullman and Julia Stiles on 'Oleanna' (October 7, 2009)

Times Topics: David Mamet

Review: 'Oleanna' (Oct. 26, 1992)

Such reflections are prompted by Doug Hughes’s revival of “Oleanna,” Mr. Mamet’s confrontational drama from 1992, which opened Sunday night at the Golden Theater in its Broadway debut. When I first saw this two-character battle of the sexes (and the classes) off Broadway at the Orpheum Theater, it seemed to move at warp speed, and I left it with shortened breath and heightened blood pressure. Yet the latest version, which pits the excellent Bill Pullman against the luminous Julia Stiles, often seemed slow to the point of stasis, and its ending found me almost drowsy.

You could attribute my reactions to various sociological and psychological factors. Many years have passed since I first saw this show. I am not the same person, and America is no longer living in the immediate shadow of the Supreme Court confirmation hearings of Clarence Thomas, when the testimony of Anita F. Hill inspired a furious national debate on sexual harassment in the workplace.

But I think the real difference in my response is less a matter of politics than of good old art and craft. The original “Oleanna,” which starred William H. Macy as John and Rebecca Pidgeon as Carol, the combative college student, was directed by its author. Mr. Mamet’s approach to staging his own plays has always been text-driven, governed by his avowed (and somewhat disingenuous) theory that if the actors just say the lines and don’t dawdle, the play will take care of itself. Under his direction “Oleanna” was, above all, a war of words colliding.

As staged by Mr. Hughes, the current “Oleanna” flies bravely in the face of Mr. Mamet’s prescriptions about acting. “There is no character,” Mr. Mamet has written. “There are only lines upon the page.” This “Oleanna” squints to read between those lines, and Mr. Pullman and Ms. Stiles have obviously been encouraged to create characters who are more than what they say.

Normally this would be a good thing. But Mr. Hughes’s “Oleanna” unwittingly makes a solid case for adhering to the Mamet method. If the “Oleanna” of 1992 left you breathless, Mr. Hughes’s measured interpretation leaves you plenty of time to breathe — and weigh and calibrate the arguments of its irrevocably opposed characters. With a set by Neil Patel that lends oddly palatial dimensions to a college professor’s office (with scenes punctuated by the ominously slow closing of tall, automated Venetian blinds), the play has been pumped full of an air of thoughtfulness that paradoxically comes close to smothering it.

That’s partly because “Oleanna” is a play about people for whom language is a conditioned reflex. They don’t think before they speak, even when they believe they do. A series of encounters between John, a professor on the verge of landing tenure, and Carol, a student on the verge of failing his class, the play is essentially an extended conversation. But it is shaped by the understanding that all conversation is potentially dangerous.

Carol comes to John’s office, distraught, to ask for a passing grade; though preoccupied with his approaching tenure confirmation and plans to buy a new house, he decides to help her. What happens after is a matter of individual interpretation, even though we see exactly what happens.

Or do we? What’s so infernally ingenious about “Oleanna” is that as its characters vivisect what we have just witnessed, we become less and less sure of what we saw. Anyway, that’s what occurs in performance — or should.

Think about it afterward, or read the script, and you’ll realize that the sympathies of Mr. Mamet, a man’s man among playwrights, are definitely with John, however flawed he may be. It also becomes clear that Carol, as a character, is full of holes, most conspicuously in the way she uses words.

All this is uncomfortably visible in Mr. Hughes’s production. Part of the problem is that Ms. Stiles is such a naturally assured, even patrician presence that it’s hard to credit her as the confused, intellectually bankrupt student of the first scene. From the beginning Carol appears to have the upper hand. (When she cries, her tears seem made of ice.)

By comparison, Mr. Pullman’s John registers as an addled, vulnerable figure. As Mr. Macy played him, John was pompous, patronizing, self-deluding and, for all his Socratic questioning, as much the prisoner of his intellectual clichés as Carol is in the later scenes, when she becomes an avatar of political correctness. Mr. Pullman puts John’s lack of confidence on the surface. He’s a chronic self-doubter, full of fear and given to mumbling, as if he doesn’t entirely trust what he says.

As he has demonstrated in first-rate portraits in Edward Albee plays (“The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?,” “Peter and Jerry”), Mr. Pullman is an expert in men who wear guilt like an undershirt. He conceives John in the same vein, and it’s a carefully thought-through, often affecting performance, climaxing in a stirring vision of a man flayed of defenses.

Yet even when things get physical between John and Carol, Mr. Pullman and Ms. Stiles never seem to connect, or even to inhabit the same universe. Each has found a personal and unorthodox way of dealing with Mr. Mamet’s fierce, fragmented language. Ms. Stiles speaks with a stiff, ladylike crispness, while Mr. Pullman gives what may be the most naturalistic line readings I’ve ever heard in a Mamet play. Neither approach is entirely appropriate to Mamet-speak, though it would help if both performances were on the same stylistic page.

Topical resonance helped make “Oleanna” famous, and it’s that aspect that the play’s producers are no doubt hoping to capitalize on with the production’s postperformance talk-back series with assorted guest celebrities (former Mayor David N. Dinkins, Kathryn Erbe of “Law & Order: Criminal Intent,” etc.). But “Oleanna” exists on its own timeless terms, and they’re defined by the power and limits of language.

With Mr. Mamet, the words really do come first. As this production demonstrates, interpreters who try to sidestep this cardinal rule do so at their peril.

OLEANNA

By David Mamet; directed by Doug Hughes; sets by Neil Patel; costumes by Catherine Zuber; lighting by Donald Holder; fight director, Rick Sordelet. Presented by Jeffrey Finn, Arlene Scanlan, Jed Bernstein, Ken Davenport, Carla Emil, Ergo Entertainment, Harbor Entertainment, Elie Hirschfeld, Rachel Hirschfeld, Hop Theatricals, Brian Fenty/Martha H. Jones and Center Theater Group. At the Golden Theater, 252 West 45th Street; (212) 239-6200. Running time: 1 hour 20 minutes.

*

Article Tools Sponsored By

By BEN BRANTLEY

Published: October 12, 2009

Here’s a little physics puzzle for John, the university professor from David Mamet’s “Oleanna” and a man who practically breaks his neck by bending it to consider questions from different angles: How is it possible that two productions of the same play — occupying roughly the same amount of stage time and using almost exactly the same words — can move at such vastly different speeds?

Skip to next paragraph

Enlarge This Image

Sara Krulwich/The New York Times

"Oleanna": Julia Stiles and Bill Pullman in a revival of the David Mamet play, at the Golden Theater.

Related

ArtsBeat: Q&A: Bill Pullman and Julia Stiles on 'Oleanna' (October 7, 2009)

Times Topics: David Mamet

Review: 'Oleanna' (Oct. 26, 1992)

Such reflections are prompted by Doug Hughes’s revival of “Oleanna,” Mr. Mamet’s confrontational drama from 1992, which opened Sunday night at the Golden Theater in its Broadway debut. When I first saw this two-character battle of the sexes (and the classes) off Broadway at the Orpheum Theater, it seemed to move at warp speed, and I left it with shortened breath and heightened blood pressure. Yet the latest version, which pits the excellent Bill Pullman against the luminous Julia Stiles, often seemed slow to the point of stasis, and its ending found me almost drowsy.

You could attribute my reactions to various sociological and psychological factors. Many years have passed since I first saw this show. I am not the same person, and America is no longer living in the immediate shadow of the Supreme Court confirmation hearings of Clarence Thomas, when the testimony of Anita F. Hill inspired a furious national debate on sexual harassment in the workplace.

But I think the real difference in my response is less a matter of politics than of good old art and craft. The original “Oleanna,” which starred William H. Macy as John and Rebecca Pidgeon as Carol, the combative college student, was directed by its author. Mr. Mamet’s approach to staging his own plays has always been text-driven, governed by his avowed (and somewhat disingenuous) theory that if the actors just say the lines and don’t dawdle, the play will take care of itself. Under his direction “Oleanna” was, above all, a war of words colliding.

As staged by Mr. Hughes, the current “Oleanna” flies bravely in the face of Mr. Mamet’s prescriptions about acting. “There is no character,” Mr. Mamet has written. “There are only lines upon the page.” This “Oleanna” squints to read between those lines, and Mr. Pullman and Ms. Stiles have obviously been encouraged to create characters who are more than what they say.

Normally this would be a good thing. But Mr. Hughes’s “Oleanna” unwittingly makes a solid case for adhering to the Mamet method. If the “Oleanna” of 1992 left you breathless, Mr. Hughes’s measured interpretation leaves you plenty of time to breathe — and weigh and calibrate the arguments of its irrevocably opposed characters. With a set by Neil Patel that lends oddly palatial dimensions to a college professor’s office (with scenes punctuated by the ominously slow closing of tall, automated Venetian blinds), the play has been pumped full of an air of thoughtfulness that paradoxically comes close to smothering it.

That’s partly because “Oleanna” is a play about people for whom language is a conditioned reflex. They don’t think before they speak, even when they believe they do. A series of encounters between John, a professor on the verge of landing tenure, and Carol, a student on the verge of failing his class, the play is essentially an extended conversation. But it is shaped by the understanding that all conversation is potentially dangerous.

Carol comes to John’s office, distraught, to ask for a passing grade; though preoccupied with his approaching tenure confirmation and plans to buy a new house, he decides to help her. What happens after is a matter of individual interpretation, even though we see exactly what happens.

Or do we? What’s so infernally ingenious about “Oleanna” is that as its characters vivisect what we have just witnessed, we become less and less sure of what we saw. Anyway, that’s what occurs in performance — or should.

Think about it afterward, or read the script, and you’ll realize that the sympathies of Mr. Mamet, a man’s man among playwrights, are definitely with John, however flawed he may be. It also becomes clear that Carol, as a character, is full of holes, most conspicuously in the way she uses words.

All this is uncomfortably visible in Mr. Hughes’s production. Part of the problem is that Ms. Stiles is such a naturally assured, even patrician presence that it’s hard to credit her as the confused, intellectually bankrupt student of the first scene. From the beginning Carol appears to have the upper hand. (When she cries, her tears seem made of ice.)

By comparison, Mr. Pullman’s John registers as an addled, vulnerable figure. As Mr. Macy played him, John was pompous, patronizing, self-deluding and, for all his Socratic questioning, as much the prisoner of his intellectual clichés as Carol is in the later scenes, when she becomes an avatar of political correctness. Mr. Pullman puts John’s lack of confidence on the surface. He’s a chronic self-doubter, full of fear and given to mumbling, as if he doesn’t entirely trust what he says.

As he has demonstrated in first-rate portraits in Edward Albee plays (“The Goat, or Who Is Sylvia?,” “Peter and Jerry”), Mr. Pullman is an expert in men who wear guilt like an undershirt. He conceives John in the same vein, and it’s a carefully thought-through, often affecting performance, climaxing in a stirring vision of a man flayed of defenses.

Yet even when things get physical between John and Carol, Mr. Pullman and Ms. Stiles never seem to connect, or even to inhabit the same universe. Each has found a personal and unorthodox way of dealing with Mr. Mamet’s fierce, fragmented language. Ms. Stiles speaks with a stiff, ladylike crispness, while Mr. Pullman gives what may be the most naturalistic line readings I’ve ever heard in a Mamet play. Neither approach is entirely appropriate to Mamet-speak, though it would help if both performances were on the same stylistic page.

Topical resonance helped make “Oleanna” famous, and it’s that aspect that the play’s producers are no doubt hoping to capitalize on with the production’s postperformance talk-back series with assorted guest celebrities (former Mayor David N. Dinkins, Kathryn Erbe of “Law & Order: Criminal Intent,” etc.). But “Oleanna” exists on its own timeless terms, and they’re defined by the power and limits of language.

With Mr. Mamet, the words really do come first. As this production demonstrates, interpreters who try to sidestep this cardinal rule do so at their peril.

OLEANNA

By David Mamet; directed by Doug Hughes; sets by Neil Patel; costumes by Catherine Zuber; lighting by Donald Holder; fight director, Rick Sordelet. Presented by Jeffrey Finn, Arlene Scanlan, Jed Bernstein, Ken Davenport, Carla Emil, Ergo Entertainment, Harbor Entertainment, Elie Hirschfeld, Rachel Hirschfeld, Hop Theatricals, Brian Fenty/Martha H. Jones and Center Theater Group. At the Golden Theater, 252 West 45th Street; (212) 239-6200. Running time: 1 hour 20 minutes.

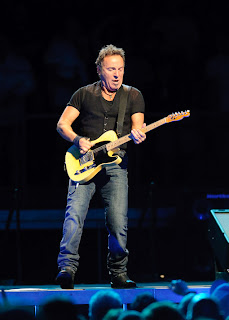

For Springsteen and Giants Stadium,

For Springsteen and Giants Stadium, a Raucous Last Dance

Todd Heisler/The New York Times

Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band played a final show at Giants Stadium on Friday.

By JON PARELES

Published: October 11, 2009

EAST RUTHERFORD, N.J. — Giants Stadium heard its last sha-la-las — at least, the amplified kind with tens of thousands of voices singing along — on Friday night, when Bruce Springsteen played the final concert before the stadium is demolished. During the three-hour set, sha-la-las filled this year’s “Working on a Dream,” the 1984 song “Darlington County” and Tom Waits’s “Jersey Girl,” the finale that Mr. Springsteen called the stadium’s “last dance.” It was Mr. Springsteen’s 24th performance since 1985 at Giants Stadium, where the audiences are his most fervent fans: fellow New Jerseyans.

Skip to next paragraph

Related

ArtsBeat: Springsteen at Giants — the Set List (October 10, 2009)

Times Topics: Bruce Springsteen

Blog

ArtsBeat

ArtsBeat

The latest on the arts, coverage of live events, critical reviews, multimedia extravaganzas and much more. Join the discussion.

* More Arts News

Enlarge This Image

Todd Heisler/The New York Times

A burst of fireworks ended the evening on Friday as Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band played Giants Stadium for the last time before its demolition.

So in a way, Mr. Springsteen could identify with the place, and he did — at least half-seriously — in “Wrecking Ball,” a robust, guitar-strumming song he wrote to start off each of his five final concerts at the stadium. (A video performance is at brucespringsteen.net.)

It may be the only song ever to make Giants Stadium itself the narrator, “raised out of steel in the swamps of Jersey.” It remembers games played and blood spilled and envisions the stadium’s fate when “all this steel and these stories, they drift away to rust/ and all our youth and beauty’s been given to the dust.” Typically, Mr. Springsteen was thinking about work, mortality and a sense of place on his way to a chorus where everyone could join in.

He wasn’t overly sentimental. Later he pointedly called Giants Stadium “the last bastion of affordable sports seating.”

At each of the Giants Stadium concerts Mr. Springsteen played one of his albums all the way through, and the one he chose for Friday was his 1984 blockbuster, “Born in the U.S.A.” Before he began the title track, he said it was “the song we started out with the first time we entered this arena.”

The album inaugurated Mr. Springsteen’s stadium era, when he strove to draw mass audiences, though still on his own terms. “Born in the U.S.A.” is an album of big riffs and broad strokes. It was also an album about home: a country (the U.S.A.), a hometown (“My Hometown”) and houses holding personal memories. And it was a paradox.

The lyrics, by and large, are about hard times and irreparable losses, even in the hits: “Born in the U.S.A.,” about a neglected Vietnam veteran, and “Dancing in the Dark,” about depression with the barest glimmer of hope. Yet most of the music is celebratory, brazening through setbacks with rock ’n’ roll: the Rolling Stones twang of “Darlington County,” the merry carousel-organ chords of “Glory Days” or the rockabilly boogie of “Working on the Highway,” which ends with its narrator in prison.

The musicians who made “Born in the U.S.A.” are all still in Mr. Springsteen’s E Street Band except for the keyboardist Danny Federici, who died last year. The concert had no celebrity guests; this was the home team.

Performing the album 25 years later, Mr. Springsteen sang with deeper nuance; he was more desperate in “Born in the U.S.A.,” angrier in “I’m Goin’ Down.” And the band has slightly bulked up the music without cluttering it. There was a seismic drum interlude by Max Weinberg in “Born in the U.S.A.,” and Nils Lofgren played frantic, searing guitar solos in “Cover Me.” The songs have not faded.

The rest of the concert spanned Mr. Springsteen’s major-label career, reaching back to “Spirit in the Night” from his 1973 debut album. It reaffirmed the band’s camaraderie; Mr. Springsteen kissed Patti Scialfa, his wife and E Street backup singer, and Clarence Clemons, the band’s saxophonist. The set riffled through styles, from the swinging “Kitty’s Back” (with Roy Bittan splashing jazzy piano chords and Mr. Springsteen playing barbed, bluesy lead guitar) to the Irish jig of “American Land” to chiming anthems like “Badlands.”

There was a glimpse of politics in “Last to Die” and a rush of redemption in “The Rising” and “Born to Run” (which had Jay Weinberg, Max’s son and occasional E Street Band replacement, on drums). And there was the constantly renewed bond between Mr. Springsteen and his audience. He strolled walkways where fans grabbed his legs, he picked up signs with requests — choosing “the perfect request for this evening,” the Rolling Stones song “The Last Time” — and he crowd-surfed in “Hungry Heart.” The video screens kept intercutting Mr. Springsteen and the musicians with fans singing verses and choruses, as if to say the songs were theirs now, too.

They were songs full of hardworking people, and Mr. Springsteen’s last goodbye to his home stadium was to them: he dedicated “Jersey Girl” to “all the crew and staff that’s worked all these years at Giants Stadium.” Some had probably been singing sha-la-la too.

Monday, October 12, 2009

whip it

Misfits With Big Hearts and Roller-Derby Grit

* Sign in to Recommend

* Twitter

*

E-MAIL

* Print

* ShareClose

o Linkedin

o Digg

o Facebook

o Mixx

o MySpace

o Yahoo! Buzz

o Permalink

o

Article Tools Sponsored By

By A. O. SCOTT

Published: October 2, 2009

Bliss Cavendar (Ellen Page) is a Texas teenager whose mother (Marcia Gay Harden) pushes her along the beauty-pageant circuit, shaking her head and pursing her lips at her daughter’s mild gestures of rebellion. But hair dye and punk rock are only the beginning. Bliss stumbles into the world of competitive women’s roller derby, which improves her self-esteem, brings her some new friends and must be kept secret from her parents. (Dad, played by Daniel Stern, is a laid-back, beer-drinking football fan in a household dominated by women.)

More About This Movie

* Overview

* Tickets & Showtimes

* New York Times Review

* Cast, Credits & Awards

* Readers' Reviews

* Trailers & Clips

View Clip...

Skip to next paragraph

Skip to next paragraph

Darren Michaels/Fox Searchlight Pictures

Related

Stepping Into the Skates of the Director (September 27, 2009)

If you think you know exactly where this story is going, you’re right. “Whip It,” the directing debut of Drew Barrymore (who shows up now and then as one of Bliss’s big-hearted, hard-riding teammates) is predictable not only in the contours of its plot, but also in nearly every scene and situation.

Bliss’s roller-derby squad, the Hurl Scouts, is a bunch of underachieving misfits with a put-upon coach (Andrew Wilson). Do they suddenly start winning, making an improbable run for the championship? What do you think? Does Bliss have a falling out and a reconciliation with her loyal, flaky best friend (Alia Shawkat)? Does Bliss meet a dreamy boy (Landon Pigg) who plays in a rock ’n’ roll band? Does she learn valuable lessons, experience laughter and tears and grow as a person? Do you have to ask?

You might, nonetheless, want to see this movie, even — or maybe especially — if you have seen “Billy Elliot” or “Bend It Like Beckham.” Familiarity is not always a bad thing, and if the script, by Shauna Cross, piles sports movie and coming-of-age touchstones into a veritable cairn of clichés, the cast shows enough agility and conviction to make them seem almost fresh. (The skating action is also fun to watch, mixing hints of sex and violence without going too far toward either.)

Ms. Page, rotating the “Juno” cool-nerd archetype a few degrees in the nice girl direction of Molly Ringwald in “Sixteen Candles,” is smart, sharp and convincing. Bliss’s pluck is appealing, but the selfishness and insensitivity that are part of any adolescent’s self-defensive armory are also very much in evidence. And Bliss’s mother, Brooke, may start out as a caricature of prim, pathological femininity, but over the course of the movie she grows in interesting directions. The debutante fantasies that hover over her pageant fixation are not pretensions, but rather the aspirations of a tough, hard-working woman (Brooke is a mail carrier) who is ultimately more clued-in and more sympathetic than Bliss gives her credit for being.

Ms. Harden is also just about the only person in the movie, which was shot in Michigan, who sounds at all Texan. (Mr. Stern tries; no one else bothers.) Wherever we’re supposed to be, the revived subculture of roller derby, a cult sport whose rules are helpfully explained by a rink-side announcer played by Jimmy Fallon, comes to exuberant if somewhat fanciful life.

The athletes have tough-sounding pseudonyms (Bliss is called Babe Ruthless), tattoos and a lot of swagger, though their sisterly, sensitive sides have a way of peeking out from behind the sweat and grime. Among the other Hurl Scouts are the rapper Eve, the stunt performer Zoe Bell (who nearly drove away with Quentin Tarantino’s “Death Proof”) and Kristen Wiig, who seems to be battling Jason Bateman and Jonah Hill for a most ubiquitous supporting actor nomination. (They’re not in this one, by the way.)

The leader of the rival squad, Iron Maven, Bliss’s nemesis, is played by Juliette Lewis, whose scenes with Ms. Page have an extra dimension of pop-culture resonance, since Ms. Lewis was the Ellen Page of an earlier era. They settle it all in a big food fight, some rough-and-tumble skating throw downs and of course a girl-to-girl heart-to-heart.

“Whip It” has an easygoing spirit, a lightness of touch in spite of occasional excursions into melodrama, that makes it hard to mock and easy to like. It will not change the way you think about movies, roller derby or the relations between teenage girls and their mothers, friends or dreams. But it does invite you to stop and appreciate all those things.

“Whip It” is rated PG-13 (Parents strongly cautioned). It has some sex and some mayhem, most of it good, clean fun.

WHIP IT

Opens on Friday nationwide.

Directed by Drew Barrymore; written by Shauna Cross, based on her novel “Derby Girl”; director of photography, Robert D. Yeoman; edited by Dylan Tichenor; music by the Section Quartet; production designer, Kevin Kavanaugh; produced by Barry Mendel; released by Fox Searchlight Pictures. Running time: 1 hour 51 minutes.

WITH: Ellen Page (Bliss Cavendar), Marcia Gay Harden (Brooke Cavendar), Kristen Wiig (Maggie Mayhem), Juliette Lewis (Iron Maven), Drew Barrymore (Smashley Simpson), Eve (Rosa Sparks), Jimmy Fallon (“Hot Tub” Johnny Rocket), Daniel Stern (Earl Cavendar), Andrew Wilson (Razor), Alia Shawkat (Pash), Landon Pigg (Oliver) and Zoe Bell (Bloody Holly).

* Sign in to Recommend

*

* ShareClose

o Linkedin

o Digg

o Facebook

o Mixx

o MySpace

o Yahoo! Buzz

o Permalink

o

Article Tools Sponsored By

By A. O. SCOTT

Published: October 2, 2009

Bliss Cavendar (Ellen Page) is a Texas teenager whose mother (Marcia Gay Harden) pushes her along the beauty-pageant circuit, shaking her head and pursing her lips at her daughter’s mild gestures of rebellion. But hair dye and punk rock are only the beginning. Bliss stumbles into the world of competitive women’s roller derby, which improves her self-esteem, brings her some new friends and must be kept secret from her parents. (Dad, played by Daniel Stern, is a laid-back, beer-drinking football fan in a household dominated by women.)

More About This Movie

* Overview

* Tickets & Showtimes

* New York Times Review

* Cast, Credits & Awards

* Readers' Reviews

* Trailers & Clips

View Clip...

Skip to next paragraph

Skip to next paragraph

Darren Michaels/Fox Searchlight Pictures

Related

Stepping Into the Skates of the Director (September 27, 2009)

If you think you know exactly where this story is going, you’re right. “Whip It,” the directing debut of Drew Barrymore (who shows up now and then as one of Bliss’s big-hearted, hard-riding teammates) is predictable not only in the contours of its plot, but also in nearly every scene and situation.

Bliss’s roller-derby squad, the Hurl Scouts, is a bunch of underachieving misfits with a put-upon coach (Andrew Wilson). Do they suddenly start winning, making an improbable run for the championship? What do you think? Does Bliss have a falling out and a reconciliation with her loyal, flaky best friend (Alia Shawkat)? Does Bliss meet a dreamy boy (Landon Pigg) who plays in a rock ’n’ roll band? Does she learn valuable lessons, experience laughter and tears and grow as a person? Do you have to ask?

You might, nonetheless, want to see this movie, even — or maybe especially — if you have seen “Billy Elliot” or “Bend It Like Beckham.” Familiarity is not always a bad thing, and if the script, by Shauna Cross, piles sports movie and coming-of-age touchstones into a veritable cairn of clichés, the cast shows enough agility and conviction to make them seem almost fresh. (The skating action is also fun to watch, mixing hints of sex and violence without going too far toward either.)

Ms. Page, rotating the “Juno” cool-nerd archetype a few degrees in the nice girl direction of Molly Ringwald in “Sixteen Candles,” is smart, sharp and convincing. Bliss’s pluck is appealing, but the selfishness and insensitivity that are part of any adolescent’s self-defensive armory are also very much in evidence. And Bliss’s mother, Brooke, may start out as a caricature of prim, pathological femininity, but over the course of the movie she grows in interesting directions. The debutante fantasies that hover over her pageant fixation are not pretensions, but rather the aspirations of a tough, hard-working woman (Brooke is a mail carrier) who is ultimately more clued-in and more sympathetic than Bliss gives her credit for being.

Ms. Harden is also just about the only person in the movie, which was shot in Michigan, who sounds at all Texan. (Mr. Stern tries; no one else bothers.) Wherever we’re supposed to be, the revived subculture of roller derby, a cult sport whose rules are helpfully explained by a rink-side announcer played by Jimmy Fallon, comes to exuberant if somewhat fanciful life.

The athletes have tough-sounding pseudonyms (Bliss is called Babe Ruthless), tattoos and a lot of swagger, though their sisterly, sensitive sides have a way of peeking out from behind the sweat and grime. Among the other Hurl Scouts are the rapper Eve, the stunt performer Zoe Bell (who nearly drove away with Quentin Tarantino’s “Death Proof”) and Kristen Wiig, who seems to be battling Jason Bateman and Jonah Hill for a most ubiquitous supporting actor nomination. (They’re not in this one, by the way.)

The leader of the rival squad, Iron Maven, Bliss’s nemesis, is played by Juliette Lewis, whose scenes with Ms. Page have an extra dimension of pop-culture resonance, since Ms. Lewis was the Ellen Page of an earlier era. They settle it all in a big food fight, some rough-and-tumble skating throw downs and of course a girl-to-girl heart-to-heart.

“Whip It” has an easygoing spirit, a lightness of touch in spite of occasional excursions into melodrama, that makes it hard to mock and easy to like. It will not change the way you think about movies, roller derby or the relations between teenage girls and their mothers, friends or dreams. But it does invite you to stop and appreciate all those things.

“Whip It” is rated PG-13 (Parents strongly cautioned). It has some sex and some mayhem, most of it good, clean fun.

WHIP IT

Opens on Friday nationwide.

Directed by Drew Barrymore; written by Shauna Cross, based on her novel “Derby Girl”; director of photography, Robert D. Yeoman; edited by Dylan Tichenor; music by the Section Quartet; production designer, Kevin Kavanaugh; produced by Barry Mendel; released by Fox Searchlight Pictures. Running time: 1 hour 51 minutes.

WITH: Ellen Page (Bliss Cavendar), Marcia Gay Harden (Brooke Cavendar), Kristen Wiig (Maggie Mayhem), Juliette Lewis (Iron Maven), Drew Barrymore (Smashley Simpson), Eve (Rosa Sparks), Jimmy Fallon (“Hot Tub” Johnny Rocket), Daniel Stern (Earl Cavendar), Andrew Wilson (Razor), Alia Shawkat (Pash), Landon Pigg (Oliver) and Zoe Bell (Bloody Holly).

good hair

Good Hair (2009)

October 9, 2009

Look but Don’t Touch: It’s All About the Hair

By JEANNETTE CATSOULIS

Published: October 9, 2009

When one of Chris Rock’s young daughters asked, “Daddy, how come I don’t have good hair?,” the comedian decided to investigate the complex, often troubled relationship between African-American women and their crowning glory. He had no idea what he was in for.

Embarking on a journey that would take him from beauty shops in the United States to a Hindu temple in India, from a hair show in Georgia to a product-manufacturing plant in North Carolina, Mr. Rock unearthed a world of physical, financial and psychological hurt. But though “Good Hair” embraces the pain, digging gingerly into wounds both political and personal, the film feels more like a celebration than a lament. Spirited, probing and frequently hilarious, it coasts on the fearless charm of its front man and the eye-opening candor of its interviewees, most of them women — including the actress Nia Long and the hip-hop stars Salt-n-Pepa — and all of them ready to dish.

In fact, one of the happy consequences of “Good Hair” should be a radical increase in white-woman empathy for their black sisters. Whether in thrall to “creamy crack,” a scary, aluminum-dissolving chemical otherwise known as relaxer (what it’s really relaxing, observes Mr. Rock astutely, is white people), or the staggeringly expensive and time-consuming weave (often available on layaway plan), the women in the film bare heads and hearts with humor and without complaint.

For the Rev. Al Sharpton, though, that’s part of the problem. “We wear our economic oppression on our heads,” he says, wryly bemoaning the migration of the multibillion-dollar, black hair-products business from African-American to predominantly Asian manufacturers. Oppression takes on a darker hue, however, when the film travels to India to unearth the unwitting — and unremunerated — suppliers of all that weave- and wig-ready hair: poor, devout women who offer it to their priests in a religious ceremony known as tonsure.

Competently directed by Jeff Stilson, “Good Hair” employs humor as a medium for insightful and often uncomfortable observations on race and conformity. The film’s only misstep is its fixation on the competitors in a flamboyant Atlanta hair show. Far more entertaining are the barbershop conversations in which ordinary men jovially gripe about their honeys’ hairdos; they’re a brotherhood joined in financial commitment and — thanks to hands-off-the-head decrees at home — emotional frustration.

On a recent “Oprah Winfrey Show,” Mr. Rock ran his fingers excitedly through his host’s luxuriant, natural tresses, unloosed in honor of the visit. “I’ve never done that to a black woman!” he marveled, while Ms. Winfrey, who used to threaten to shave her head when she reached her 50th birthday, giggled delightedly: at that moment, she was just happy not to have followed through with her threat.

“Good Hair” is rated PG-13 (Parents strongly cautioned). Chemical treatments and revolutionary sentiments.

Good Hair

Opens on Friday nationwide. Directed by Jeff Stilson; written by Chris Rock, Mr. Stilson, Lance Crouther and Chuck Sklar; director of photography, Cliff Charles; edited by Paul Marchand and Greg Nash; music by Marcus Miller; produced by Nelson George, Mr. Rock and Kevin O’Donnell; released by Roadside Attractions. Running time: 1 hour 35 minutes.

October 9, 2009

Look but Don’t Touch: It’s All About the Hair

By JEANNETTE CATSOULIS

Published: October 9, 2009

When one of Chris Rock’s young daughters asked, “Daddy, how come I don’t have good hair?,” the comedian decided to investigate the complex, often troubled relationship between African-American women and their crowning glory. He had no idea what he was in for.

Embarking on a journey that would take him from beauty shops in the United States to a Hindu temple in India, from a hair show in Georgia to a product-manufacturing plant in North Carolina, Mr. Rock unearthed a world of physical, financial and psychological hurt. But though “Good Hair” embraces the pain, digging gingerly into wounds both political and personal, the film feels more like a celebration than a lament. Spirited, probing and frequently hilarious, it coasts on the fearless charm of its front man and the eye-opening candor of its interviewees, most of them women — including the actress Nia Long and the hip-hop stars Salt-n-Pepa — and all of them ready to dish.

In fact, one of the happy consequences of “Good Hair” should be a radical increase in white-woman empathy for their black sisters. Whether in thrall to “creamy crack,” a scary, aluminum-dissolving chemical otherwise known as relaxer (what it’s really relaxing, observes Mr. Rock astutely, is white people), or the staggeringly expensive and time-consuming weave (often available on layaway plan), the women in the film bare heads and hearts with humor and without complaint.

For the Rev. Al Sharpton, though, that’s part of the problem. “We wear our economic oppression on our heads,” he says, wryly bemoaning the migration of the multibillion-dollar, black hair-products business from African-American to predominantly Asian manufacturers. Oppression takes on a darker hue, however, when the film travels to India to unearth the unwitting — and unremunerated — suppliers of all that weave- and wig-ready hair: poor, devout women who offer it to their priests in a religious ceremony known as tonsure.

Competently directed by Jeff Stilson, “Good Hair” employs humor as a medium for insightful and often uncomfortable observations on race and conformity. The film’s only misstep is its fixation on the competitors in a flamboyant Atlanta hair show. Far more entertaining are the barbershop conversations in which ordinary men jovially gripe about their honeys’ hairdos; they’re a brotherhood joined in financial commitment and — thanks to hands-off-the-head decrees at home — emotional frustration.

On a recent “Oprah Winfrey Show,” Mr. Rock ran his fingers excitedly through his host’s luxuriant, natural tresses, unloosed in honor of the visit. “I’ve never done that to a black woman!” he marveled, while Ms. Winfrey, who used to threaten to shave her head when she reached her 50th birthday, giggled delightedly: at that moment, she was just happy not to have followed through with her threat.

“Good Hair” is rated PG-13 (Parents strongly cautioned). Chemical treatments and revolutionary sentiments.

Good Hair

Opens on Friday nationwide. Directed by Jeff Stilson; written by Chris Rock, Mr. Stilson, Lance Crouther and Chuck Sklar; director of photography, Cliff Charles; edited by Paul Marchand and Greg Nash; music by Marcus Miller; produced by Nelson George, Mr. Rock and Kevin O’Donnell; released by Roadside Attractions. Running time: 1 hour 35 minutes.

Ghosts in the Family, the Helpful Sort, on Call

By NATE CHINEN

Published: October 11, 2009

During the final moments of her sold-out concert at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn on Friday night, Rosanne Cash stood beneath an image of her with her father, Johnny Cash. It was a photograph projected on a backdrop, and it faded soon enough to feel like a mirage. Given that Ms. Cash had just sung “Sweet Memories,” a country ballad of haunted remembrance, that apparitional suggestion was on the mark.

Skip to next paragraph

Enlarge This Image

Michael Nagle for The New York Times

Rosanne Cash performing at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn.

In another sense, her father, who died in 2003, had been present throughout the show. Ms. Cash was inaugurating the 30th-anniversary season of St. Ann’s Warehouse with a program inspired by her new album, “The List” (Manhattan). It’s an object lesson in inheritance: in 1973, when Ms. Cash was a teenager on the road with her father, he drew up a list of 100 essential country songs she should seek out and absorb. The album features a dozen of them, performed with loving humility by Ms. Cash and a handful of guests, including Bruce Springsteen and Elvis Costello.

On Friday she worked without any outside help. (“Is Bruce here?” she quipped, looking around. “I think Bruce is playing a larger venue tonight,” she added, alluding to Giants Stadium.) She was more than capable of carrying the material herself, backed by a precise and flexible band. Her husband, John Leventhal, who produced the album, doubled as lead guitarist and musical director.

Ms. Cash has a voice both dark and sweet, with a gentle but reliable vibrato, and she knows how to convey the quiet sting of heartache. She made “Motherless Children,” a traditional song, feel hard and unsparing; her take on “Long Black Veil,” which she described as the album’s centerpiece, was chilling in its tranquillity. Before singing “Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow,” a Carter Family song, she recalled how Helen Carter had helped her learn to play guitar, backstage over the course of a tour. (Ms. Cash is the stepdaughter of June Carter Cash, Helen’s sister.)

A serious songwriter herself, Ms. Cash took a well-considered detour at the concert’s midpoint, lighting on the title tracks of two acclaimed albums, “Seven Year Ache” (1981) and “The Wheel” (1993). But she allowed the shadow of her father to creep into even some of the originals, like “Radio Operator,” a rockabilly vignette inspired by the courtship of her parents. Written with Mr. Leventhal, it appears on her 2006 album, “Black Cadillac” (Capitol), which she presented at St. Ann’s Warehouse that year.

Another “Black Cadillac” selection, “The World Unseen,” came about as close as possible to illuminating the evening’s purpose. Over a bittersweet country-rock groove, Ms. Cash created an evocative scene: an empty room, a night sky, the distant sound of a guitar. “So I will look for you,” she sighed, “between the grooves of songs we sing.”

By NATE CHINEN

Published: October 11, 2009

During the final moments of her sold-out concert at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn on Friday night, Rosanne Cash stood beneath an image of her with her father, Johnny Cash. It was a photograph projected on a backdrop, and it faded soon enough to feel like a mirage. Given that Ms. Cash had just sung “Sweet Memories,” a country ballad of haunted remembrance, that apparitional suggestion was on the mark.

Skip to next paragraph

Enlarge This Image

Michael Nagle for The New York Times

Rosanne Cash performing at St. Ann’s Warehouse in Brooklyn.

In another sense, her father, who died in 2003, had been present throughout the show. Ms. Cash was inaugurating the 30th-anniversary season of St. Ann’s Warehouse with a program inspired by her new album, “The List” (Manhattan). It’s an object lesson in inheritance: in 1973, when Ms. Cash was a teenager on the road with her father, he drew up a list of 100 essential country songs she should seek out and absorb. The album features a dozen of them, performed with loving humility by Ms. Cash and a handful of guests, including Bruce Springsteen and Elvis Costello.

On Friday she worked without any outside help. (“Is Bruce here?” she quipped, looking around. “I think Bruce is playing a larger venue tonight,” she added, alluding to Giants Stadium.) She was more than capable of carrying the material herself, backed by a precise and flexible band. Her husband, John Leventhal, who produced the album, doubled as lead guitarist and musical director.

Ms. Cash has a voice both dark and sweet, with a gentle but reliable vibrato, and she knows how to convey the quiet sting of heartache. She made “Motherless Children,” a traditional song, feel hard and unsparing; her take on “Long Black Veil,” which she described as the album’s centerpiece, was chilling in its tranquillity. Before singing “Bury Me Under the Weeping Willow,” a Carter Family song, she recalled how Helen Carter had helped her learn to play guitar, backstage over the course of a tour. (Ms. Cash is the stepdaughter of June Carter Cash, Helen’s sister.)

A serious songwriter herself, Ms. Cash took a well-considered detour at the concert’s midpoint, lighting on the title tracks of two acclaimed albums, “Seven Year Ache” (1981) and “The Wheel” (1993). But she allowed the shadow of her father to creep into even some of the originals, like “Radio Operator,” a rockabilly vignette inspired by the courtship of her parents. Written with Mr. Leventhal, it appears on her 2006 album, “Black Cadillac” (Capitol), which she presented at St. Ann’s Warehouse that year.

Another “Black Cadillac” selection, “The World Unseen,” came about as close as possible to illuminating the evening’s purpose. Over a bittersweet country-rock groove, Ms. Cash created an evocative scene: an empty room, a night sky, the distant sound of a guitar. “So I will look for you,” she sighed, “between the grooves of songs we sing.”

Sunday, October 11, 2009

Friday, October 09, 2009

dream

I have been dreaming of alternate side parking, natalie merchant again and various woman who were looking for various sexual encounters. ...

These HRT are kicking in... and at least I am sleeping deeply and dreaming

These HRT are kicking in... and at least I am sleeping deeply and dreaming

Persons I fun into

I left work late yesterday after stopping to chat and as I was leaving the building, I ran into one of my current students. James works near me and was walking to the train. We talked about class, his social work experience and I supported his efforts. We talked about the daily articles I send out and how they are useful to him. He is not computer literate and is learning to read them on line.

Capricorn Horoscope for week of October 8, 2009

Capricorn Horoscope for week of October 8, 2009

John, a colleague of mine, is a skillful psychotherapist. His father is in a similar occupation, psychoanalysis. If you ask John whether his dad gave him a good understanding of the human psyche while he was growing up, John quotes the old maxim: "The shoemaker's son has no shoes." Is there any comparable theme in your own life, Capricorn? Some talent or knowledge or knack that should have been but was not a part of your inheritance; a natural gift you were somehow cheated out of in your early environment? If so, the coming weeks will be an excellent time to start recovering from your loss and getting the good stuff you have coming to you.

John, a colleague of mine, is a skillful psychotherapist. His father is in a similar occupation, psychoanalysis. If you ask John whether his dad gave him a good understanding of the human psyche while he was growing up, John quotes the old maxim: "The shoemaker's son has no shoes." Is there any comparable theme in your own life, Capricorn? Some talent or knowledge or knack that should have been but was not a part of your inheritance; a natural gift you were somehow cheated out of in your early environment? If so, the coming weeks will be an excellent time to start recovering from your loss and getting the good stuff you have coming to you.

john lennon birthday

imagine peace news

THE ROCK & ROLL HALL OF FAME ANNEX NYC WILL OFFER FREE ADMISSION ON OCTOBER 9th AND 10TH IN HONOR OF JOHN LENNON’S BIRTHDAY

A SPECIAL GIFT TO FANS

NEW YORK, NY (October 7, 2009) – The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Annex NYC will offer fans free admission on October 9th and 10th to provide the ideal place to pay special tribute to legendary artist, John Lennon on what would have been his 69th birthday. The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame Annex NYC showcases rare artifacts from legendary artists including Springsteen, The Beatles, Bob Dylan, the Rolling Stones and its featured exhibit, JOHN LENNON: THE NEW YORK CITY YEARS.

JOHN LENNON: THE NEW YORK CITY YEARS represents a decade of freedom in New York City during the era of love, peace and rock & roll. The exhibition was made possible through the generosity of Yoko Ono, the wife and widow of Lennon. The exhibit is on loan to the Annex by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. and was curated by Ms. Ono and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum’s Vice President of Exhibitions and Curatorial Affairs, Jim Henke. The exhibit includes a selection of rare artifacts, films and photos as well as exclusive New York-centric additions provided by Yoko Ono.